Momentum, the tendency for recent performance to persist in the short term, is one of the most pervasive forces in financial markets. It is difficult to reconcile with the efficient-market hypothesis, which predicts that market prices reflect all publicly available information, including past performance. In fact, Eugene Fama and Ken French, two leading proponents of the efficient-market hypothesis, have called it the premier market anomaly.

There are three potential behavioral biases that could cause momentum: anchoring, disposition, and herding. The first two cause prices to initially adjust to new information more slowly than they should (under-reaction), while the third leads to over-reaction. Anchoring is based on the idea that investors ground their investment thesis in information they already know and are slow to update their view in response to new information. This phenomenon is consistent with post-earnings-announcement drift, a situation in which firms beat (or miss) earnings expectations, and their stocks pop (or drop) on the day they make that announcement, but continue to outperform (or underperform) during the subsequent several weeks.

The disposition effect describes many investors’ tendency to sell stocks whose prices have increased in order to lock in profits and hold on to stocks that have declined in value in the hope of breaking even, despite changing fundamentals. This behavior is related to loss aversion, where the pain of losing money exceeds the utility from an equal-sized gain. Like anchoring, this can cause prices to adjust more slowly than they should in the face of changing fundamentals, as investors exhibiting this behavior make their trading decisions based on the price that they paid for a security rather than its fundamental value.

Once a trend is established, investors may chase performance and pile into the trade, which could push prices away from fair value (herding behavior). This could lead to the long-term performance reversals associated with the value effect. These long-term reversals make long-term performance chasing counterproductive.

Momentum is a short-term phenomenon, where relative performance during the past six to 12 months tends to persist over the next several months. Academic studies most commonly measure momentum based on performance during the past 12 months, excluding the most recent one (though the effect persists even without this exclusion), and rebalance monthly.

While investors should arbitrage any predictable pricing pattern away, momentum has persisted more than two decades after it was first widely documented in the academic literature. It is difficult to fully arbitrage because it requires high turnover, which can make the strategy difficult and costly to implement, and it doesn’t always pay off. Simple momentum strategies often don’t work well when volatility picks up, or during sharp market reversals, when performance leadership changes. Just like any other investment strategy, momentum carries its own risks.

Momentum strategies often target individual securities. But momentum also works at the sector, country, and asset-class levels where implementation costs should be lower, as it isn’t necessary to trade as many securities. To illustrate, I tested three momentum strategies using sector, country, and asset-class indexes that investors can gain access to through exchange-traded funds. However, it is important to keep in mind that these are still high-turnover strategies that would be best implemented in tax-advantaged accounts.

Sector Strategy

To assess whether it is possible to profit from sector level momentum, I ran an analysis using the 10 Dow Jones U.S. sector indexes. I chose these particular indexes because they have the longest history of any set of equity sector benchmarks. IShares’ U.S. equity sector ETFs track these indexes, but Vanguard and the Select Sector SPDR ETFs offer similar exposure with lower fees.

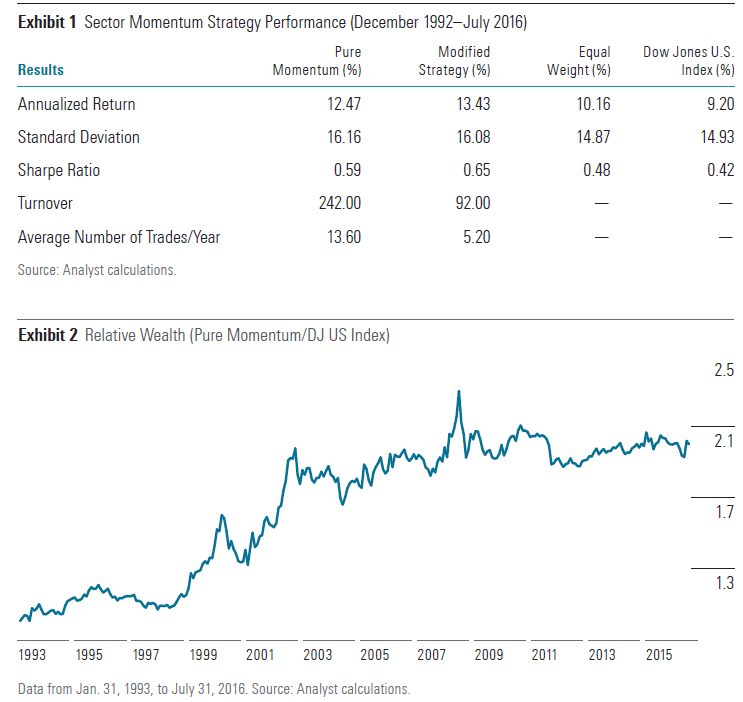

Each month, I ranked the indexes by their returns during the past 12 months and selected the three with the best returns. I initially equally weighted these holdings but did not rebalance them until they were removed from the portfolio. For instance, if two positions were sold, the proceeds would be divided equally between the two new holdings. However, the existing holding would remain in the portfolio at its current weighting. This approach reduces turnover and makes the strategy easier and less costly to implement. The portfolio simulation began in December 1992 (using index return data starting in December 1991, the earliest available) and ran through July 2016. This strategy is labeled pure momentum in the table below, which illustrates the results.

The strategy outpaced the broad, market-cap-weighted Dow Jones U.S. Index and an equally weighted portfolio of the 10 sector indexes by 3.3 and 2.36 percentage points annualized, respectively, with slightly greater volatility. Much of this outperformance occurred between 1998 and June 2008, as the Exhibit 2 shows. The strategy fared less well during the trailing five years through July 2016, during which time it lagged the index by 91 basis points annualized. This illustrates that, although the momentum strategy has tended to work well over the long term, it can experience long periods of underperformance.

This strategy offers clean exposure to the momentum effect because it aggressively rebalances each month and quickly dumps holdings that are no longer among the strongest recent performers. But it also requires high turnover, which can erode returns in practice. On average, the strategy required 13.6 trades each year, for a turnover ratio of 242%.

However, it is possible to modify the strategy to reduce turnover. To accomplish this, I reconstituted the momentum portfolio quarterly, instead of monthly, and implemented a buffering rule. As long as the existing holdings’ performance ranked in the top four of the 10 indexes, I would not sell them because they would still have decent momentum. If there were fewer than three indexes that satisfied that condition, I would select the top-ranking indexes remaining until the portfolio had three.

These adjustments cut turnover by more than half, requiring an average of 5.2 trades per year, as the data in the Modified Strategy column in the table above show. And the strategy still outperformed the market-cap-weighted index by a considerable margin. It was somewhat surprising that the modified strategy did a little better than the original because it is less style-pure, though this result is probably not significant. The important point is that these modest adjustments should improve cost efficiency, making it easier to profit from momentum in practice.

In part 2 of this article, we will talk about the remaining Harnessing Momentum