In part 1, we started looking at the relationship between dividend yields and interest-rate sensitivity. In this part, we dive deeper by connecting the dots with companies’ fundamentals.

Sorting on Size

To better understand the relationship between dividend yields and interest-rate sensitivity, we need to connect the dots with companies' fundamentals. Dividends are often a sign of maturity. As companies progress through their life cycles, their growth slows and reinvestment needs decline, allowing them to distribute more cash. Using market cap as a proxy for maturity, this evolution is evident.

Exhibit 3 shows the results of a regression analysis I ran on SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY, listed in the U.S.), SPDR S&P MidCap 400 ETF (MDY, listed in the U.S.), and SPDR S&P 600 Small Cap ETF (SLY, listed in the U.S.). I used these funds as proxies for their respective strata of the market-cap ladder. As was the case with the output featured in Exhibit 2 in Part 1, I used the market risk premium and monthly changes in the 10-year Treasury yield as explanatory variables.

The relationships here are clear. Large caps tend to be less sensitive to the market than their smaller-cap peers and shows a negative relationship with changes in interest rates . This aligns well with the general characteristics of larger firms relative to their smaller counterparts. Specifically, they tend to be more mature and better capitalized, and may have more-diverse revenue sources. These attributes lend themselves to less market sensitivity and a greater ability and propensity to return cash to shareholders via regular dividends.

Sorting by Industry

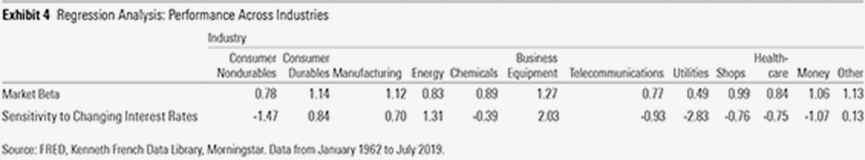

While looking at interest-rate sensitivity across market-cap strata helps ground this relationship in firms' fundamentals, the picture is still far from complete. Zooming in further and examining how this relationship varies across industries paints a more vivid portrait. Exhibit 4 contains the results of a regression analysis I ran for 12 industry portfolios sourced from Kenneth French's Data Library. Once again, I used the market risk premium and monthly changes in the 10-year Treasury yield as explanatory variables.

Those industries that are generally deemed defensive in nature--owing to inelastic demand for their offerings and ample pricing power--are most sensitive to changes in interest rates. These include utilities and consumer nondurable goods. Companies operating in these industries tend to produce steadier cash flows, and thus tend to suffer as rates rise and get a boost when they fall. More-cyclical industries like business equipment and manufacturing exhibit the opposite relationship. Demand for their output tends to ebb and flow with economic output, as do their cash flows. As such, they tend to get a tailwind from rising rates (which tend to be indicative of a growing economy, inflation, or both) and are hamstrung when they fall (often coincident with a softening economy).

Don't Sweat Rising Rates

It can be helpful to understand how dividend-paying stocks and the funds that own them are affected by fluctuating rates. But it's important not to conflate awareness and understanding with a call to action. Rates will rise and fall, and no one knows when or by how much. Owning quality companies that regularly return cash to shareholders is a solid strategy for all rate environments.

.png)