Interest rates influence the prices and expected returns of nearly every investment. Low and falling rates tend to inflate asset prices but reduce their future returns. That makes investors feel richer today but increases the challenge of growing wealth and generating income in the future. Rising rates have the opposite effect.

It was once unthinkable that interest rates would remain as low as they have for as long as they have, or that the Federal Reserve would cut the federal-funds rate below 2% with unemployment below 4%. While it's tough to predict what will happen to interest rates, investors shouldn't count on rates reverting to their historical norms. They can remain low for a long time, particularly when inflation expectations are low, as they are now. In Japan, short-term rates have been below 1% for more than 20 years.

There's nothing you can do to change interest rates or easily overcome the challenges low rates create. It's better to adjust expectations about the returns your investments can offer and determine whether they provide sufficient compensation for their risk.

Term Risk

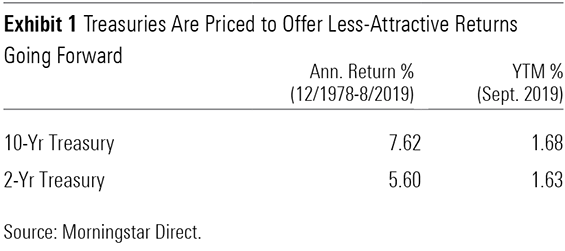

Currently, term risk doesn't pay well. Term risk is the extra interest-rate sensitivity that long-term bonds carry relative to short-term bonds. When interest rates rise, long-term bonds' prices tend to fall more than short-term bonds'. So, they should offer higher expected returns to compensate, and historically they have, as Exhibit 1 shows.

Most of the time, long-term bonds offer higher yields than short-term bonds. However, the Treasury yield curve, which plots the yields of Treasury bonds across the maturity spectrum, is currently fairly flat.

The shape of the yield curve reflects both the term risk premium and the market's expectations of future short-term rates. If the market expects short-term rates to fall significantly, the yield curve could slope down, even if long-term bonds offer a term premium. In that case, long-term bonds would still be priced to offer better returns than investing in short-term bonds and rolling the proceeds over to a successive series of newly issued short-term bonds at maturity, owing to future rate cuts. Typically, such cuts coincide with slowing economic growth, so an inverted yield curve is often interpreted as a sign of trouble ahead.

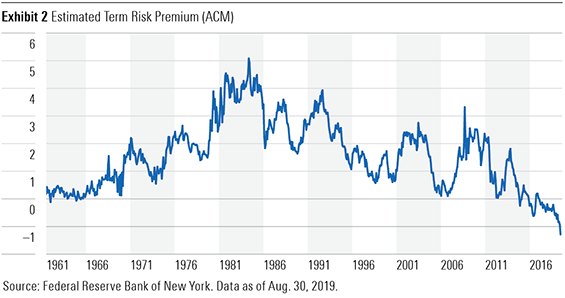

The term premium isn't directly observable, but an econometric model developed by economists at the New York Fed suggests that it has become negative in recent years, as shown in Exhibit 2. It's hard to explain why. However, the negative premium may be attributable to low inflation expectations, central bank purchases of long-term bonds, a desire to lock in long-term returns, and low rates in other countries.

With a negative term premium, it's more likely for the yield curve to be flat or inverted. The curve could be inverted if investors expect interest rates to remain flat or even rise slightly, which reduces its power to predict recessions. A negative term premium also suggests, even when the yield curve is sloping upward, that investors could earn higher returns by investing in short-term bonds and rolling those funds into newly issued short-term bonds at maturity than investing in long-term bonds.

Because long-term rates are low and the estimated term premium is negative, it may be prudent to consider tilting toward short-term bonds.

However, some caveats are in order. Short-term bonds have greater reinvestment rate risk than long-term bonds, creating greater uncertainty about the long-term return investors can get from them. And while short-term bonds tend to do better relative to long-term bonds when the yield spread between them is smaller, that relationship is noisy. So, long-term bonds can still offer higher returns even when the curve is flat.

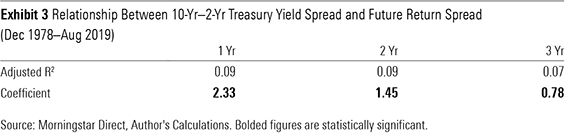

A regression analysis revealed that the yield spread between 10-year and two-year Treasuries explained less than 10% of the subsequent return difference between those bonds over the next few years, as shown in Exhibit 3. That's because the shape of the yield curve changes over time, which changes short and long-term bonds' returns relative to each other.

That said, the relationship between long- and short-term spreads and future returns was statistically significant (so it probably wasn't attributable to chance) and went in the expected direction. The results were similar using the estimated term premium in place of the simple yield spread.

In Part 2 of this article, we will also look at credit risk.

.png)