In part 1 of the article, we looked at the case for value investing and the requirements for value investing to work. In this part, we continue by discussing the risk of value investing and looking at why value has underperformed.

Risk

The risk of value investing is real, as the past 13 years have shown. Look no further than the coronavirus-driven sell-off. From Feb. 19 through March 24, 2020, the Russell 3000 Value Index lost 32.2%, 7 percentage points more than its growth counterpart. Value stocks tend to have weaker fundamentals than growth stocks. They are less likely to enjoy durable competitive advantages and tend to be less profitable with less favorable outlooks. They also tend to have more fixed assets, which can make them less flexible and potentially more susceptible to recessions.

Hertz is a good case in point. This car rental company is a small-value stock that recently filed for bankruptcy protection, as its vast fleet of cars sat unused when travel largely dried up during the coronavirus pandemic. While diversified portfolios of value stocks have little exposure to firm-specific risk, some risks are common across most value stocks and cannot be fully diversified away. So, it’s reasonable that investors would require compensation for holding this risk.

Why Has Value Underperformed?

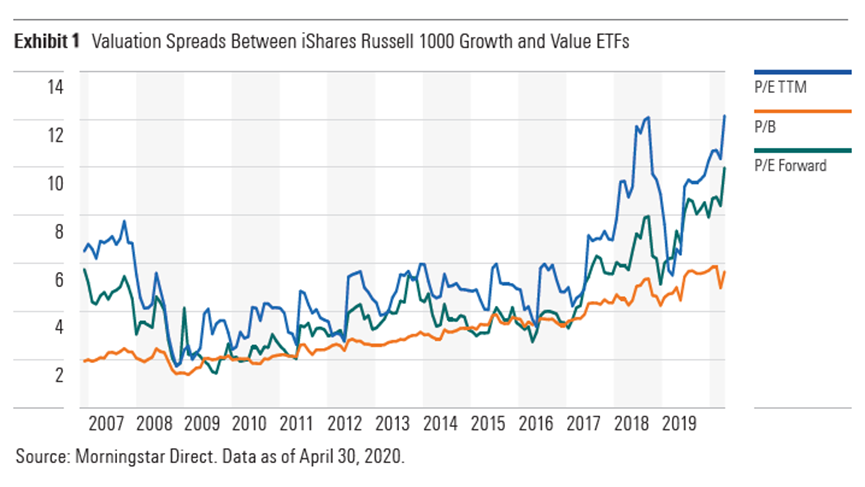

If the case for owning value stocks hasn’t fundamentally changed, why has it underperformed for so long? The chief reason is that they’ve gotten cheaper relative to growth stocks, as Exhibit 1 shows. It’s possible that change is justified by widening spreads in future cash flows between value and growth stocks. However, this may also be a sign that investors have become overly pessimistic about value stocks. Either way, the valuation gap can’t grow indefinitely, so this headwind should subside at some point.

Portfolio Construction and Size Matter

While there are strong theoretical underpinnings for value investing, traditional broad large-value index funds probably aren’t the best way to take advantage of the value effect. Small-value stocks are the better bet, as they tend to carry greater risk for which investors require compensation and are more susceptible to mispricing.

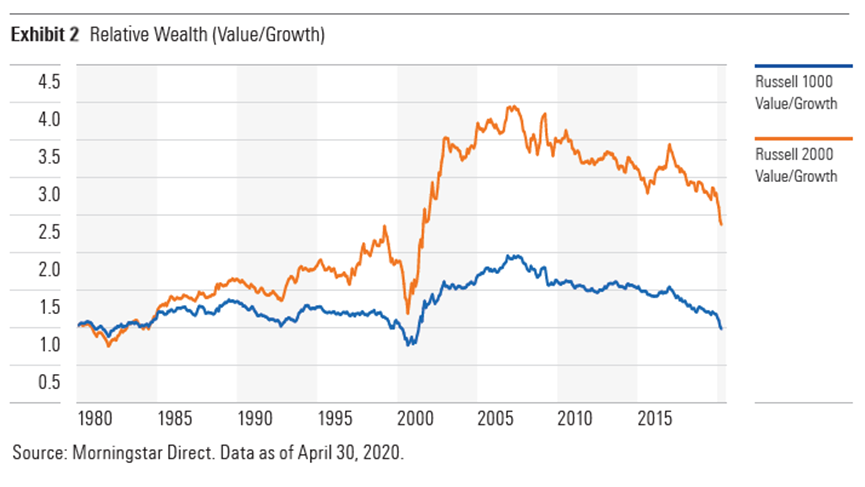

Consider the Russell 1000 Value Index, which targets stocks representing the cheaper and slower-growing half of the U.S. large-cap market. From its inception at the end of 1978 through April 2020, this index slightly lagged its growth counterpart by 13 basis points annualized. During that span, the Russell 2000 Value Index, which applies the same construction rules to the U.S. small-cap market, beat its growth counterpart by 2.3 percentage points annualized. Exhibit 2 shows the relative wealth of an investment in each value index compared with its corresponding growth index.

Value investing can still work in large-cap stocks, but portfolio construction choices matter. The metrics index providers use to define value and growth may seem like an important differentiator. Yet differences in metrics across index providers don’t appear to make a big difference, as standard valuation metrics tend to be highly correlated. What moves the needle more is whether the index uses a sector-relative approach to stock selection and how aggressively it pursues value.

Most of the return benefit from owning value stocks appears to have come from intrasector stock selection.3 Looking at valuations within each sector should facilitate cleaner comparisons and mitigate persistent sector biases that are a source of active risk that the market may not reward.

The MSCI USA Enhanced Value Index demonstrates how a sector-relative approach to value investing can help. (The iShares Edge MSCI USA Value Factor ETF (VLUE, U.S.-listed)tracks this index.) From its inception at the end of November 1997 through April 2020, this sector-neutral index beat the standard MSCI USA Value Index by 2.3 percentage points annualized. While it had greater exposure to growth-oriented sectors like technology, the MSCI USA Enhanced Value Index tended to have a more pronounced value tilt than the MSCI USA Value Index, owing to its narrower portfolio and use of valuations to size positions.

Value investing hasn’t lost its luster, but it’s necessary to be patient and selective about how you invest in value stocks. While value will likely make a comeback, it’s hard to know when. Diversification is always a good idea. It’s best to use value alongside other factor strategies, like momentum and quality, to reduce the pain of underperformance when it inevitably comes.

3 Bryan, A., & McCullough, A. 2017. “The Impact of Industry Tilts on Factor Performance.” Morningstar. https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/ shared/pdfs/Research/The_Impact_of_Industry_Tilts_on_Factor_Performance.pdf

.png)