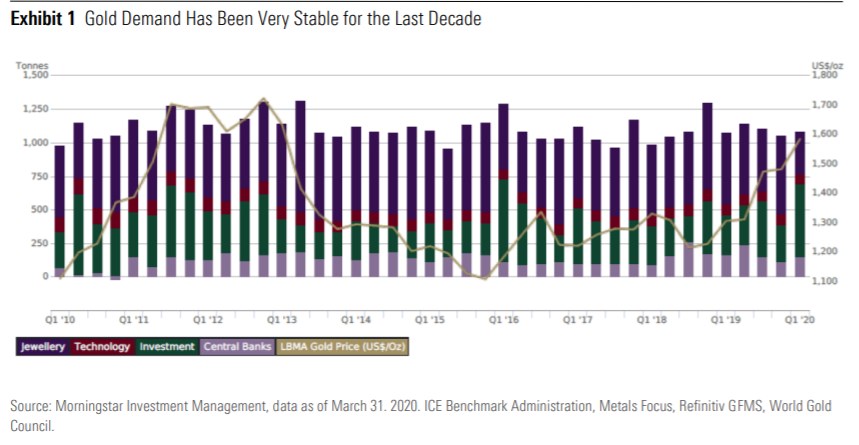

One word that many investors have used to describe 2020 is ‘volatile’. The year has been marked by uncertainty and volatility. The market highs of February were followed by the coronavirus pandemic and a subsequent downturn—but one that was short-lived. In the middle of all this turmoil, investors sought a safe haven—and seemed to find it in gold.

Investors seem to love the metal and want to buy, but we don’t think it is a good idea to invest in gold. We even busted the myth that you need to invest in gold—you don’t. Commodities like gold have little intrinsic value. Returns are governed by the balance of demand and supply, with a fair amount of speculation thrown in. These factors are extremely difficult, if not impossible, for retail investors to predict, so the chances of success are extremely low.

None of this has deterred investors. Even long-term gold cynic Warren Buffett made news headlines recently when it was announced that his company, Berkshire Hathaway, added a small stake in Toronto-based Barrick Gold (one of the world’s largest gold producers) to its portfolio in the second quarter of the year.

“Is buying gold speculation, or can we call it an ‘investment’? On one hand, gold doesn’t produce cash flows, so can’t be valued. Or said another way—its price varies based on something other than its ability to provide investors future cash flows. This makes it a challenging asset for investors (especially for valuation-driven investors like us), with any investment thesis relying instead on supply/demand inputs and price discovery based on what the next investor thinks it is worth,” says Morningstar Investment Management’s global head of research, Philip Straehl, in a recent report titled, “Understanding Gold: An Expensive Insurance Policy?”

He points out that these characteristics limit an investor’s ability to assess a potential investment, creating a wider range of potential outcomes than, say, bonds. On this basis, investor sentiment is a difficult variable and gold does have a history of enduring major setbacks, with drawdowns of over 10% not uncommon.

Gold as a Safe Haven

On the other side, gold has a long and alluring history as a safe-haven investment.

Morningstar equity analyst Kristoffer Inton classifies an asset as a safe haven if it holds, or even increases, its value during periods of market and economic uncertainty and downturns. The asset should preserve capital, withstand market volatility, and provide diversification across a portfolio.

He assesses the viability of any asset class as a safe haven by identifying whether the asset class has five main characteristics: liquidity, functional purpose, scarcity of supply, future demand certainty, and permanence. On all five characteristics, gold meets the definition of a safe haven.

“Gold has also traditionally been a refuge against U.S. dollar weakness, largely due to the inverse relationship between what is generally accepted as the world’s reserve currency and commodity prices,” points out Straehl.

Protection Against Market Declines

Straehl notes that gold has created a reputation for excelling during periods of significant market declines and periods of unusually high market volatility.

“More recently, the COVID-19 sell-off provided an interesting case study in that although gold fared better than stocks, it still posted a small loss during the ‘panic phase’. Market commentators have attributed this to many factors, including the fact that the sell-off was liquidity-driven (and therefore all encompassing) and the feeling that interest-rate cuts will support the U.S. dollar (a negative for commodity prices). Lockdown measures introduced across the globe also caused mine closures and production shutdowns, which affected gold producers negatively. Gold did, however, reverse course, moving significantly higher in the months following the market sell-off,” he says.

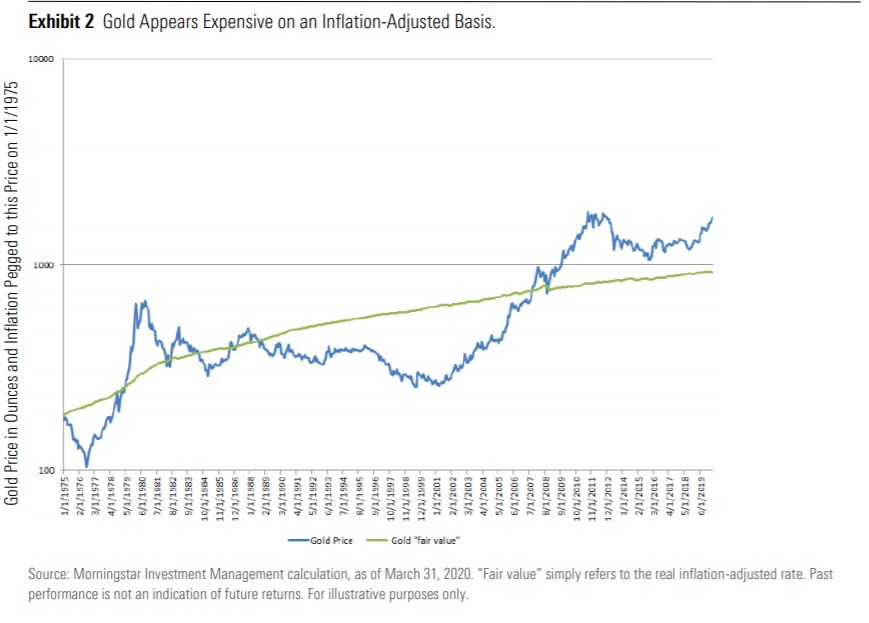

However, despite often being regarded as a hedge against inflation, Straehl points out that gold’s record of protection is rather mixed.

“The metal did provide significant protection during the high inflationary period of the 1970s, when higher oil prices and an expanding money supply pushed inflation to extreme levels in the United States and elsewhere. During more muted periods of inflation, including the early 1980s and between 1988-91, gold delivered negative returns, lagging equity markets in the process. Given the unprecedented levels of fiscal stimulus delivered by major central banks and governments in response to the pandemic, concerns have been raised that this may lead to a significant uptick in inflation. While this may be true, the evidence suggests that gold’s role as an inflation hedge may be overdone and that there is no guarantee that the metal will provide protection if inflation becomes a problem,” he says.

He adds that on a real basis after inflation, gold is already expensive and could therefore suffer a material drawdown.

What’s the Bottom Line?

“On a forward-looking basis, it is not conclusive that adding gold allocations to a portfolio will be beneficial, especially given the drawdown risk it may face. Gold does not produce any cash flows and could experience a meaningful drawdown from current levels. While an investor might expect gold to keep up with inflation in the very long run, the strongest evidence for holding gold appears to be as a safe haven in periods of significant market volatility. In this sense, it may be better viewed as an expensive insurance policy rather than a core holding,” Straehl says.

.png)