The S&P 500 Equal Weight Index is one example of a much larger subset of alternatively weighted strategies that have historically beaten the market. In “The Surprising Alpha From Malkiel’s Monkey and Upside-Down Strategies,” [1] researchers from Research Affiliates examined different ways to weight stocks, including volatility (both high and low), earnings growth, and fundamentals (among others). All of these alternatively weighted strategies outperformed a market-cap-weighted index because they all tilted toward stocks with smaller market capitalizations and lower valuations, even if the tilt was unintentional.

The researchers went a step further and inverted the weight of each stock in these alternative strategies. Intuitively, if the alternative strategies beat the market, then inverting the weights should cause them to underperform. But surprisingly, the inverse portfolios also leaned toward stocks with smaller market capitalizations and lower valuations and wound up beating the market-cap-weighted portfolio.

The researchers then tested randomly assembled portfolios to further test this phenomenon and reached the same conclusion. In short, just about any strategy that did not weight its holdings by market capitalization ended up tilting toward stocks with smaller market capitalizations and lower valuations, which helped them outperform a market-cap-weighted benchmark. Had value and small size not paid off, the story probably would have been different.

Beyond Factors

There is one more twist to this story. Some of these alternatively weighted strategies can gain an advantage through fortuitous timing of their rebalancing activity. Mechanically shifting assets away from companies that have become more expensive and toward those that are now cheaper can be an advantage when the market’s valuation reaches extremes (either too expensive or too cheap).

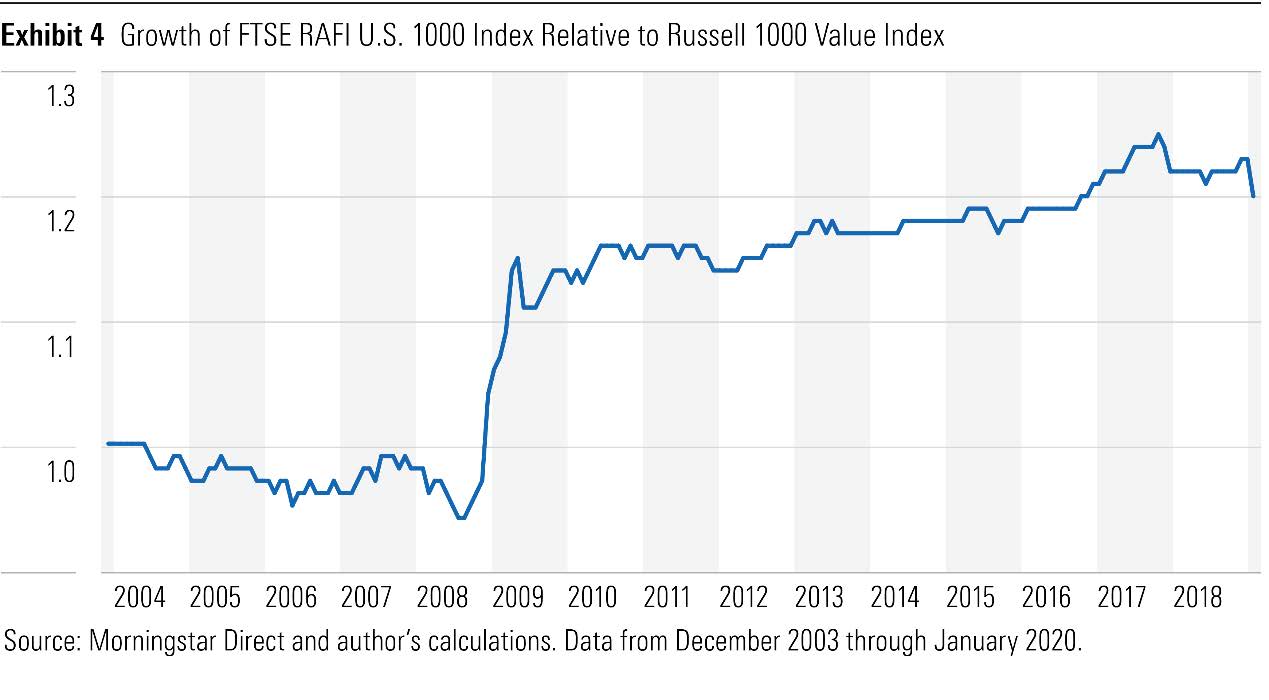

For example, The FTSE RAFI U.S. 1000 Index weights its holdings by several fundamental metrics. This causes it to increase its weight on stocks as their price declines relative to those fundamentals, making it a value strategy. It happens to reconstitute annually on the third Friday in March--a date that closely aligned with the U.S. market’s inflection point in 2009. Rebalancing at that time caused it overweight the cheapest stocks when prices were near their low point, meaning they had the most to offer as prices appreciated.

The effect of rebalancing near the market low is evident in Exhibit 4, which charts the growth of the FTSE RAFI U.S. 1000 Index relative to the market-cap-weighted Russell 1000 Value Index. Both indexes provided similar performance when the line was flat. The RAFI Index outperformed when the line sloped upward and underperformed when it sloped downward. The sharp upward slope between April and October 2009 was the only period where it had a significant advantage over the market-cap-weighted Russell 1000 Value Index.

The caveat with this outperformance is that the rebalance needs to be timed so that it coincides with mean-reversion in valuations, which often occurs when there’s a change in the direction of the market. But it’s nearly impossible to predict when those inflection points will occur. Thus, the surge of outperformance over those seven months in 2009 isn’t representative of what the strategy typically delivers. Rebalancing away from expensive stocks and into cheaper ones can still provide an advantage when valuations mean revert, but the benefit will likely be less significant in trending markets.

The caveat with this outperformance is that the rebalance needs to be timed so that it coincides with mean-reversion in valuations, which often occurs when there’s a change in the direction of the market. But it’s nearly impossible to predict when those inflection points will occur. Thus, the surge of outperformance over those seven months in 2009 isn’t representative of what the strategy typically delivers. Rebalancing away from expensive stocks and into cheaper ones can still provide an advantage when valuations mean revert, but the benefit will likely be less significant in trending markets.

No Snowflakes Here

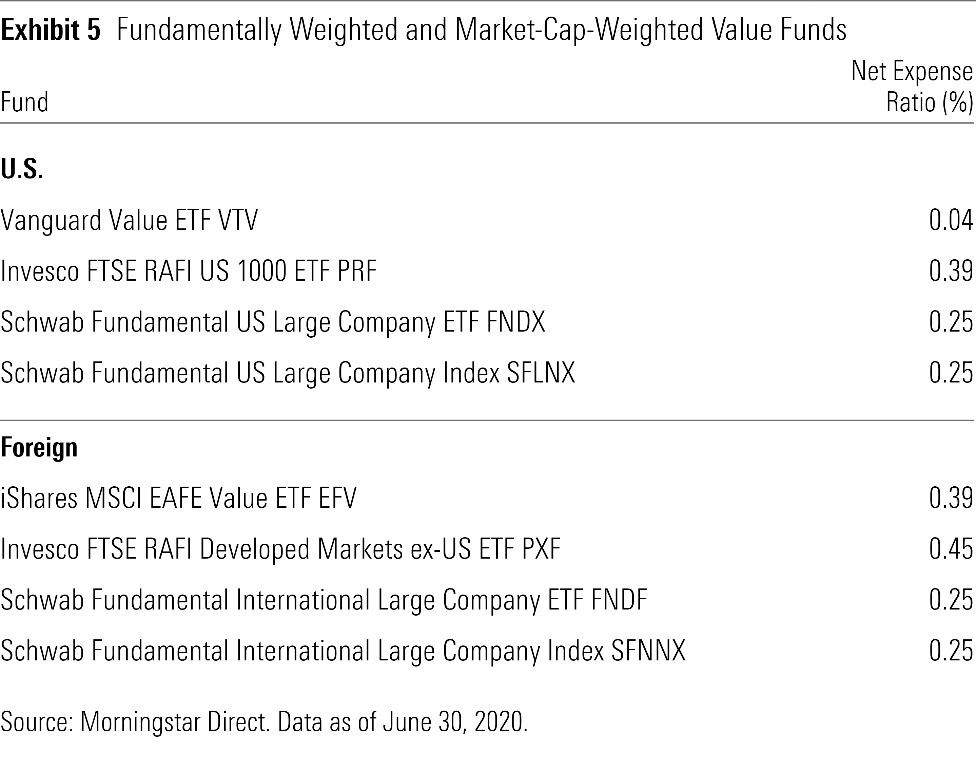

The evidence suggests that there’s nothing special about most alternatively weighted strategies. They’re often just repackaged versions of the size and value factors. The factor exposures that they provide should be tempered against their fees because there may be a cheaper and more consistent way to access the same factors.

For instance, in the U.S. Vanguard Value ETF (VTV) provides exposure to U.S. value stocks for just 0.04% annually while the fundamentally weighted strategies from Invesco and Schwab, which provide similar value exposure, charge 0.39% and 0.25%, respectively. However, Schwab’s fundamentally weighted index strategies offer a cheaper way to get exposure to the value factor among foreign developed stocks than the only available market-cap-weighted value ETF, iShares MSCI EAFE Value ETF (EFV), as Exhibit 5 shows.

[1] Arnott, Robert D., Jason Hsu, Vitali Kalesnik, and Phil Tindall. 2013. “The Surprising Alpha From Malkiel’s Monkey and Upside-Down Strategies.” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol 39, No. 4.

.png)